Henry IV, Part 1

Henry IV, Part 1, chronicle play in five acts by William Shakespeare, written about 1596–97 and published from a reliable authorial draft in a 1598 quarto edition. Henry IV, Part 1 is the second in a sequence of four history plays (the others being Richard II, Henry IV, Part 2, and Henry V). Known collectively as the “second tetralogy,” the plays depict major events of English history in the late 14th and early 15th centuries. While King Henry IV is the titular character, much of the action in Henry IV, Part 1 and its sequel, Henry IV, Part 2, center on the king’s son, Prince Hal, who becomes the titular character in Henry V. The group of plays is often referred to as “the Henriad.”

The historical facts in the play were taken primarily from Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles (1577), but Sir John Falstaff and his cronies in Eastcheap (an area in London) are original creations (with some indebtedness to popular traditions about Prince Hal’s prodigal youth that had been incorporated into a play of the 1580s called The Famous Victories of Henry the Fifth) who add an element of robust comedy to Henry IV that is missing in Shakespeare’s earlier chronicles.

Plot

Set in a kingdom plagued with rebellion, treachery, and shifting alliances in the period following the deposition of King Richard II, the two parts of Henry IV focus especially on the development of Prince Hal (later Henry V) from wastrel to ruler rather than on the title character. Indeed, King Henry IV is often overshadowed not only by his son but also by Hotspur, the young rebel military leader, and by Hal’s roguish companion Falstaff. Secondary characters (many of them comic) are numerous. The plot shifts rapidly between scenes of raucous comedy and the war against the alliance of the Welsh and the rebellious Percy family of Northumberland.

A tale of fathers and sons (Act I)

Hotspur, whom Henry IV admiringly describes as “gallant,” bases his rebellion on the conviction that Edmund Mortimer is the rightful monarch. He believes that Richard II had named Mortimer as his heir before Bolingbroke, who ascended the throne as Henry IV, usurped power. Later in the play, Henry IV offers a pardon and redress of the rebels’ grievances. However, Hotspur’s uncle—the earl of Worcester, who acts as his emissary—deliberately withholds the king’s offer of pardon, prompting Hotspur to prepare for battle.

As Part 1 begins, Henry IV, wearied from the strife that has accompanied his accession to the throne, is renewing his earlier vow to make a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. He learns that Owen Glendower, the Welsh chieftain, has captured Edmund Mortimer, the earl of March, and that Henry Percy, known as Hotspur, son of the earl of Northumberland, has refused to release his Scottish prisoners until the king has ransomed Mortimer. Henry laments that his own son, Prince Hal, is not like the fearless Hotspur:

Yea, there thou mak’st me sad, and mak’st me sin

In envy that my Lord Northumberland

Should be the father to so blest a son,

A son who is the theme of Honor’s tongue,

Amongst a grove the very straightest plant,

Who is sweet Fortune’s minion and her pride;

Whilst I, by looking on the praise of him,

See riot and dishonor stain the brow

Of my young Harry. O, that it could be proved

That some night-tripping fairy had exchanged

In cradle-clothes our children where they lay,

And called mine “Percy,” his “Plantagenet”!

Then would I have his Harry, and he mine.

As the war escalates, Glendower, Mortimer (now married to Glendower’s daughter), and Hotspur (now allied with the Welsh) conspire to divide Henry’s kingdom into three equal parts.

Hal and Falstaff’s dissolute lifestyle (Act II)

Meanwhile, Prince Hal and his cronies, including the fat, boisterous Falstaff and his red-nosed sidekick, Bardolph, have been drinking and playing childish pranks at Mistress Quickly’s inn at Eastcheap. Hal, who admits in an aside that he is consorting with these thieving rogues only temporarily, nevertheless agrees to take part with them in an actual highway robbery. He does so under certain conditions: the money is to be taken away from Falstaff and his companions by Prince Hal and his comrade Poins in disguise, and the money is then to be returned to its rightful owners, so that the whole caper is a practical joke on Falstaff rather than a robbery. This merriment is interrupted by Hal’s being called to his father’s aid in the war against the Welsh and the Percys.

Falstaff asks Hal to watch over him in the Battle of Shrewsbury and then delivers a monologue on the futility of dying for a concept so abstract as honor:

The redemption of Hal and death of Hotspur (Acts III–V)

Hal and his father manage to make up their differences, and Hal vows to defeat Hotspur. Northumberland sends his son, Hotspur, a message claiming that he is too ill to join the rebels. Hal saves his father’s life in combat and further proves his valor in battle. He chides Falstaff for malingering and drunkenness and then kills Hotspur in personal combat during the Battle of Shrewsbury. Hal laments the wasteful death of his noble opponent and of Falstaff, who lies on the ground nearby. But Falstaff is only feigning death, and, when he claims to have killed Hotspur, Hal agrees to support the lie. At the play’s end, the rebellion has been only temporarily defeated.

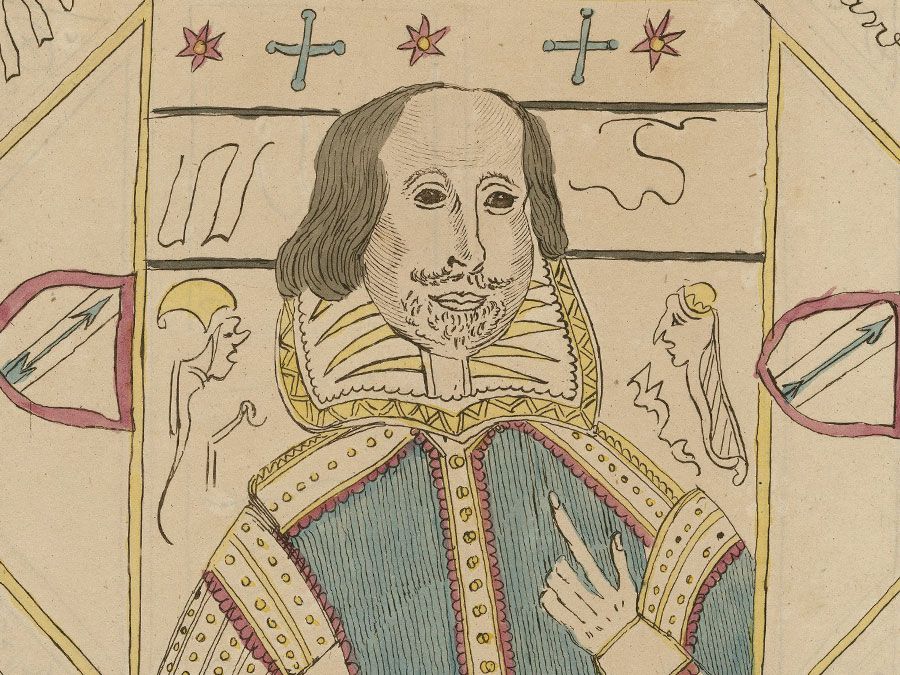

For a discussion of this play within the context of Shakespeare’s entire corpus, see William Shakespeare: Shakespeare’s plays and poems.